Everyone gets too many emails every day. A good subject line helps organize and triage the inbox so we don’t get overwhelmed.

Then WHY OH WHY do you still send emails with these remarkably stupid and useless subject lines?

- Thanks

- Following up

- Quick question

- Checking in

- Hey

- Got a sec?

Ok, that last one at least passes one (maybe two) of the five tests for an adequate subject line. The rest tell me nothing about the email, but they tell me the sender did not give any thought to how I interact with email. These are the opposite of clickbait. Clickbait infuriates me with its tease–I know that the article won’t live up to its hype-saturated headline–but I sometimes can’t help myself, and I click anyway.

These subject lines infuriate me with their lazy uselessness, yet I know I must read them, even if they turn out to be throwaway nothingness. Because behind these vapid subjects may be a critical business task. There’s no way to tell.

These subject lines infuriate me with their lazy uselessness, yet I know I must read them, even if they turn out to be throwaway nothingness. Because behind these vapid subjects may be a critical business task. There’s no way to tell.

So. Five rules. Here they are:

- Tell me what’s in the email

“Quick question” may hint at it, but I have never in my life met a quick question that had a quick answer. My day is a constant barrage of incoming problems, and I cannot triage effectively if I don’t know what you’re emailing me about. - If it’s time-sensitive, say so

Add something like URGENT: to let me know that this requires attention now. The priority flag in most email programs like Outlook help, but adding this will make it unambiguous. Better: add the timeframe. NEED TODAY or NEED BY JUNE 16 makes it easy to triage and makes it pop out if it scrolls below the fold. - If it requires action, say so

Correllary to the prior point, ACTION REQUIRED: at the beginning of a subject line lets me know that something needs to get done. An approval, perhaps, or a compliance step that may be holding up the project. - If it requires my attention specifically, say so

If you send an email to 100 people with ACTION REQUIRED and only one of them needs to take action, you deserve a time out. FRED ACTION REQUIRED lets everyone know that Fred is on the hook, but the rest of us have a need to know. Maybe to make sure Fred does his job. - Be unique

Once four different people emailed on different topics, all with the subject line “Following up.” Soon, more than twenty emails clogged my inbox with the subject line “Re: Following up”. Most were reply-all “thanks, great to meet you, too!” One thread was about a timely, critical problem. Guess how much time I wasted wading through the sludge to handle the real problem.

It should go without saying that not every email is TIME SENSITIVE ACTION REQUIRED red-flag emergency.

Also, when writing subject lines, assume the recipient has a smaller screen than you do. “Following up on the meeting about action required time sensitive stuff” will show up on a phone as “Following up on…” Entirely useless and very difficult for a busy person to track effectively.

Good communication is not about how you say something; it’s about how the recipient experiences it. Too many people treat writing email subjects like picking the color of an envelope. Marketing experts know, however, there’s an art to designing the packaging in order to get the recipient to care about the contents before they even open the package. Junk mail is often designed to look overly important, to get you to open it. Well designed packaging lets you know what you’re getting before you open it, and helps you manage your inbox effectively.

Pay attention to the subject lines of emails you send and receive over the next week, and note how you and others respond to them. Do you have tips on writing good subject lines, or examples of really bad ones? Share!

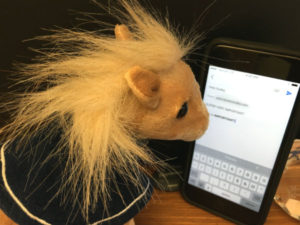

The Editing Pony

The Editing Pony is a blog series about good business writing. I’ll post periodic tips and gladly critique and rewrite emails or one-pagers for you in a blog post. Contact me to learn more.

The Editing Pony is a blog series about good business writing. I’ll post periodic tips and gladly critique and rewrite emails or one-pagers for you in a blog post. Contact me to learn more.

Why a pony? A writer friend said she hadn’t edited in ages, but she was “getting back up on that pony.” Thus, the Editing Pony was conceived, to trample your words with ruthless, plush cuteness.